Have We Been Saying The Lord’s Prayer All Wrong?

The Lord’s Prayer has a reassuring ring for Roman Catholics who recite it in English. The Shakespearean style of its opening lines — “Our Father, who art in Heaven, hallowed be Thy name … ” — suggests something ancient and unchanging.

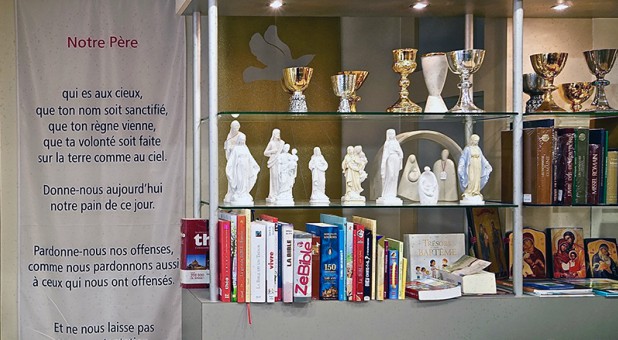

In other languages, however, translations of the prayer Jesus taught to his disciples are now the subject of lively debate. The French recently updated theirs, and the Italians will opt for their own new version later this year, while the Germans have just said a firm “nein” to any change.

Pope Francis, who in his native Spanish prays a version that is slightly different again, encouraged proponents of a new translation in December when he praised the changes made in French.

But another reform the Argentine pontiff has championed — giving local church hierarchies a greater say in how the original Latin texts of prayers are translated — gave the German bishops the leeway to refuse to follow the suggestion he made.

Welcome to the confusing world of Catholic translations, where linguistics, theology, ecumenism and power politics clash despite the church’s claim to universalism. (The term “Catholic” comes from the Greek word for universal.)

The problem arises from the fact that Jesus would have recited his prayer in Aramaic or Hebrew, but it was reported in the Gospels in Greek and later translated into the Roman church’s official language, Latin.

A key point of discord: The Latin text of the prayer’s sixth petition to God is “ne nos inducas in tentationem” (“lead us not into temptation”), while the Greek original, which ends with the word “peirasmos,” can also be translated as a “trial” or “test of faith.”

Some non-Catholic churches have been more flexible with that line and focused on the Greek version. An ecumenical translation by liturgists from around the English-speaking world translated it as “save us from the time of trial.”

But Catholic congregations, which recite the prayer at Mass, want to avoid straying too far from the Latin. Theologians disagree on how to transfer that phrase from a dead language into living modern tongues.

The current confusion began when Catholic bishops in France switched to a new translation on Dec. 3, changing the sixth petition from “Do not submit us to temptation” — the wording they have used since the 1960s — to “Let us not enter into temptation.”

They argued that God would not tempt his faithful into sin, so a new translation was needed to avoid the impression that he would willingly do the devil’s work.

French-speaking Catholics in Belgium and Benin had already introduced the change in June 2017, but seeing it happen in much larger France attracted attention in the wider Catholic world.

In an interview with the Italian Catholic television station TV2000 a few days later, Pope Francis approved the French move and agreed the older version was faulty.

“(God) is not the one who pushes me into temptation,” he said. “A father does not do that. … The one who leads into temptation is Satan.”

Francis actually misquoted the new French translation, explaining in Italian that it said “do not let us fall into temptation.” That is the way this line is translated in Spanish and Portuguese.

The Catholic Church in Italy proposed almost a decade ago to replace “do not lead us into temptation” with the phrase “do not abandon us to temptation,” but only announced last week that its bishops would meet in November to approve its use at Mass.

Italian theologians began working on the change as early as 1988 and its bishops approved it in 2002, Cardinal Giuseppe Betori of Florence told the Italian daily Avvenire in December.

But a Vatican directive in 2001 titled Liturgiam Authenticam stated that all translations of prayers must be as close as possible to the original Latin, which forced local churches to review all the work they had recently done and get approval from Rome for the slightest change.

Denounced by critics as a bid by conservatives in the Vatican to exert control over national churches around the world, this led to years of haggling between Rome and commissions of bishops from the major language groups.

Vatican authorities insisted on translations that critics in several language groups, especially English, thought sounded stilted to native speakers and were hard to recite out loud.

Pope Francis, who frequently criticizes Vatican centralization, acted to end this tension in September by issuing an edict saying that national bishops conferences would from now on decide how to render prayers from Latin into their own languages.

Cardinal Robert Sarah, the conservative head of the Vatican department that oversees translations, claimed in October that his office still had the power to impose its versions on recalcitrant bishops. A week later, the pope took the unusual step of publicly telling Sarah he was wrong.

One effect of this devolution of responsibility became clear last week when the German bishops conference, an influential subgroup within the world Catholic hierarchy, announced it did not agree with the objections that others — including the pope — had to the traditional translation of the Our Father.

“The petition ‘lead us not into temptation’ … does not express the suspicion that God could want people to fail, but the belief in his justice and mercy,” it said in a five-page statement explaining why it would not change its translation.

The statement mentioned ecumenical reasons for sticking with the old version. Bishop Heinrich Bedford-Strohm, head of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD), had said a week before that churches could not simply rewrite biblical texts.

But it also posed a problem for German-speaking Austria, where Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna agreed with Pope Francis shortly after the pontiff’s interview. The bishops conference there now has to decide whether to follow the pontiff’s advice or to keep in step with its larger neighbor and not change anything.

In countries with two or more languages, Catholics can pray differently according to where they live. In Belgium, the Wallonia region adopted the new French translation while Flanders switched in 2016 to a new Dutch translation that says “bring us not to the test.”

Switzerland has a German-speaking majority that has not changed its Our Father, a Francophone minority that will follow the French example at Easter this year and an Italian-speaking minority that will make the switch when Italy does.

The Rev. Adrian Schenker, an emeritus professor of Old Testament studies at Switzerland’s University of Fribourg, found a way to say that both the old and new translations were correct.

Both versions would be possible if the petition were translated back into Jesus’ native tongue, Aramaic, or the Hebrew used for prayers in the synagogue, so his original words could have been understood both ways, the Dominican theologian wrote in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

“Both translations and both understandings are possible and so they must have been intended,” he said. “Wherever the Biblical speech has several meanings, we must understand it in its ambiguity.” {eoa}

© 2018 Religion News Service. All rights reserved.